The Rural Decline: A Blog Series

The rural decline is a global phenomenon, and it is inevitable during a country’s development. In this blog series, we will identify the definitions of urban, rural and their linkage, show why protecting the interactions between urban and rural is important and how the rural decline can harm the interactions. We will also use three different cases (Canada, Spain, Vietnam) to discuss what triggered the problem, how governments reacted. Ultimately, we will use these example to share insights and lessons learned on the rural decline.

Urban, rural and their linkage

Though the terms ‘rural’ and ‘urban’ are well-known, their definitions do not converge. Different countries may use different measurements (e.g., population, accessibility to public service, agriculture employment, etc.) to classify an area. Even if two countries use the same measurement, the thresholds can be different. For example, in China, an area with at least 100,000 people is classified as a city. The requirement is only 200 in Denmark. A uniform classification system that can be globally applied is essential for cross-country research.

Recently, the World Bank developed a new indicator to facilitate comparability across countries called the Degree of Urbanization. The indicator characterises an area into one of the three types of settlements: cities,;towns and semi-dense areas; and rural areas. The indicator is a simple combination of population size and density as follows:

Cities have a lower threshold of 50,000 on inhabitants and a lower threshold 1,500 of inhabitants per km2 on population density.

Towns and semi-dense areas have a lower threshold of 50,00 on inhabitants and a lower threshold of 300 inhabitants per km2 on population density.

Rural areas, any area does not belong to the above two groups.

Using population related data to classify an area is widely accepted and the data is relatively accessible. But it does not mean that the indicator is flawless. Two areas with the same level of urbanisation can be classified into different types of settlements, especially for the areas with indicators near the thresholds.

Rural-urban interactions

In recent years, the interactions and interrelations between the rural and urban area has attracted the attention of researchers. The reason is simple: they are indeed closely related, and macro policies that neglect their impacts on the interactions can result in severe problems like over-populated cities and rural depopulation. A detailed review by Tacoli (1998) lists some empirical studies on how growing social polarisation are linked to the deterioration of rural-urban linkage in the following aspects: flows connecting two areas (people, goods, waste) and sectoral interactions (urban agriculture, non-agricultural rural employment, and interlinkages in peri-urban areas). The most intuitive one is the flow of people. The traditional view is that it is triggered by the “push-pull” factors. Push factors consist of the hardships of living in rural areas, which includes lower income and lower accessibility to essential services. Pull factors consist of the comparative advantages of living in cities, which includes more opportunities and higher income. Individuals are rational decision-makers, and they choose the best place to live. The more factors there are, the larger migration can be observed.

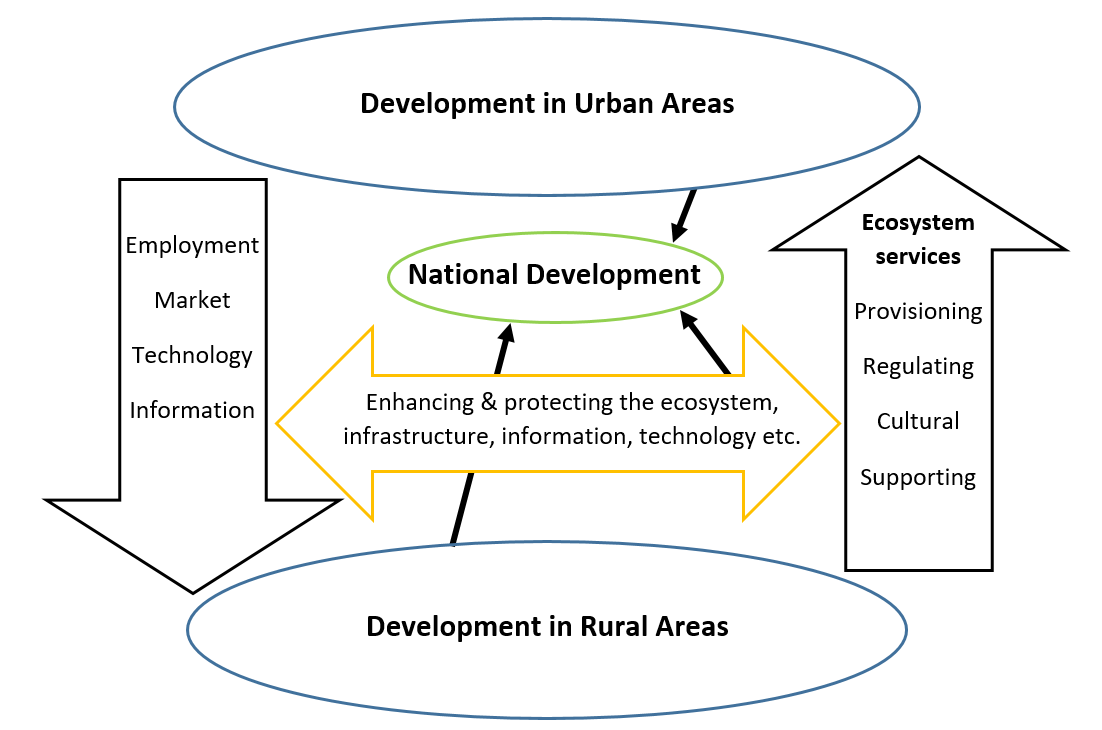

These interactions are later called ecosystem services and the entire urban-rural linkage is captured in the framework in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Conceptual framework of ecosystem based rural-urban linkages (Gebre & Gebremedhin, 2019)

Urban areas can provide employment, market demand, technology, and information to rural areas. Our main aim is to accentuate the ecosystem services provided by the rural area, which can benefit the entire system and are usually overlooked by policymakers. The provisioning services consist of the basic goods provided by rural populations, which include food, water, raw materials (timber, fibre), energy, etc. The Regulating services relate to climate control and waste management. Cultural services are the intangible benefits from the natural environment (tourism and recreation). Supporting services are more general, which relates to the services that can support the maintenance of other services (nutrient cycling, biological diversity, habitat formation, etc.).

Overview of spatial planning policies

Spatial planning policies are influenced by two different theories of economic development. The first prioritises the agriculture sector, it claims that the surplus of agricultural products are the preliminaries for industrial and urban development. On the contrary, the second claims that a more modern and productive agricultural sector requests industrial growth.

Before the mid-1960s, rural out-migration was regarded as a positive process since the industrialization progress in the agriculture sector allowed the transfer of labour from rural areas without declines in agriculture productivity. The replacement of the traditional sector by the modern emerging sector is natural. At the time, the policies gave properties to the cities. However, by the end of the decade, the fast-going urban population could not be fully absorbed by the manufacturing sector and new job opportunities in the modern sector were much lower than expected. Governments started to concern the pressure on over-populated urban cities and strategies on counter urbanisation, which include the management of balanced growth of urban and rural areas.

Challenges

Here, a global challenge called rural decline is discussed. Rural decline is an abstract word to describe the erosion of rural areas, which is mainly reflected in depopulation, increasing unemployment, community destruction, shrinking public services, economic depression and deteriorating quality of life in rural areas. It is a crucial problem since the rural-urban interactions are worsened.

Figure 2: The changes of rural population proportions in the world, 1981-2016 Li, et al, (2019)

Before the industrial revolution, about 97% of the worlds’ population was living in the countryside. The low productivity, poor transportation and communication limited the interaction between the rural residents and the urban residents. The coming development of technology broke the obstacles. Rural areas, particularly the agriculture-based and far away from the urban regions experienced decline. As Figure 2 shows, during 1981-2016, most countries in the world experienced rapid rural depopulation. This phenomenon is especially prevalent in the rapidly developing countries, which include east and south Asia, north and south Africa and Latin America.

Conclusion

The long-lasting biased policies, which prioritise the development of urban areas, break rural areas’ ability to provide ecosystem services and further destroy the interactions between the two areas. The global rural depopulation is one of the results. In fact, the reasons for rural depopulation can be quite different in different countries. Hence, we have picked three case studies with vastly different socio-economic development statuses and regional profiles. In our next blog post, we will dive into Canada, Spain and Vietnam in detail and analyse their rural decline problems later.