How Poverty Trap Theory Guides Poverty Alleviation Policies

In 1960, per capita incomes in Burundi, Haiti and Nicaragua were $347, $1,512, and $2,491, respectively. After fifty years of development, these three nations had seen very little changes in their per capita incomes, totalling to $396, $1411, and $2,289. Meanwhile, the income in the US, Australia and Canada had tripled. While the other countries are experiencing continuous growth, why are the poor trapped in poverty? Figure 1 illustrates the average real GDP per capita of the top 20 richest countries while Figure 2 illustrates that of the top 20 poorest countries. A comparison of both figures indicates wide income disparity.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 3 (1) shows the contrast between the top 5 richest/poorest countries and the top 10 richest/poorest countries - demonstrating the neglectable income increases in the post-war era.

The poverty trap is a term to describe a situation where poverty is self-reinforcing. Poverty trap theory uses economic models to explain how persistent poverty forms and what policies can be implemented to help the trapped countries overcome this issue. The theory is developed from the Solow model, which acts as one of the foundations of macroeconomics.

Solow Model

Figure 4

The Solow model is a traditional model portraying long-run economic growth (2). The diminishing marginal return on production factors results in a globally concave production function and guarantees a unique equilibrium. See Figure 4, in which Gk,1 is the augmented capital accumulation equation.

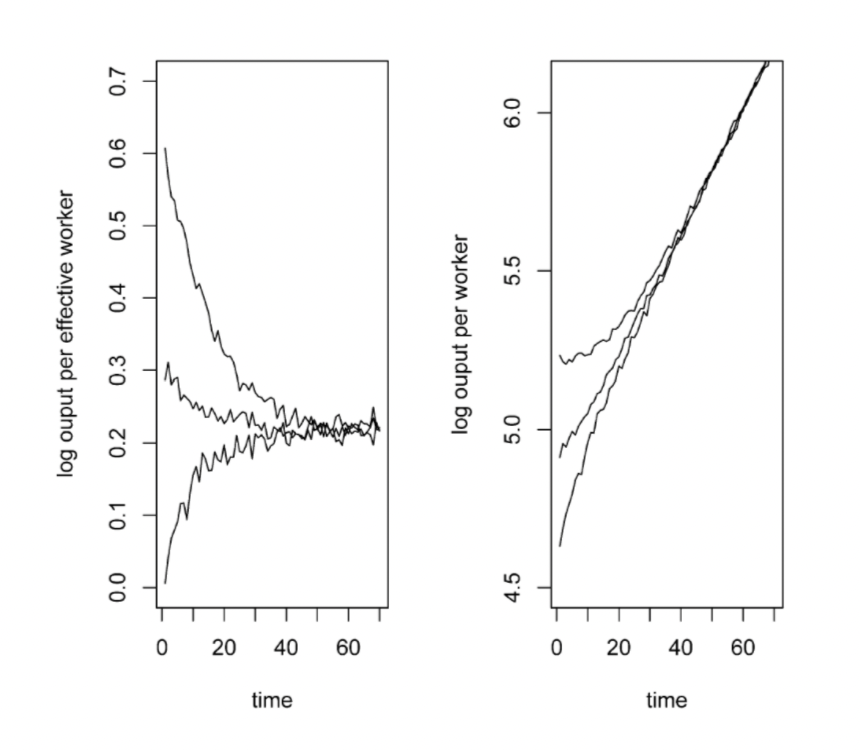

The implications are: Given the three exogenously determined variables (saving rate, fertility rate and technology growth rate), all countries should converge to the same balanced growth path, which is irrelevant to the initial endowment. Countries with lower initial capital should experience a higher return on investment according to this model, while countries with higher initial capital should experience lower returns. Thus, they would be expected to converge paths after a period of time, resulting in similar levels of per capita income. See Figure 5, in which three countries are given different initial capital endowments.

Figure 5

However, many countries (such as Nepal, El Salvador, Mozambique and Bangladesh) did not experience the growth that should have happened according to the Solow model (3) and remain trapped in poverty , as Figure 5 shows. As a result, some of the basic assumptions of the Solow model must deviate from reality.

Poverty Trap Theory

There are many reasons why we observe non-convergence. Ghatak (4) classifies these reasons into two categories: 1. Scarcity-driven poverty trap. 2. Frictional-driven poverty trap. The first model tries to blame the poverty trap on the lack of income, time, attention span, etc. For example, lower-income households will spend a larger proportion of their income on consumption (5). This results in a lower saving rate and a poorer equilibrium. In the Scarcity-driven poverty trap theory, an individual’s choice plays an important role. It claims that the poor suffer from special constraints which drives them to make decisions that reinforce poverty. The mainstream research focuses on the second type.

Figure 6

Frictional-driven poverty trap

The second type blames the poverty trap on external frictions which limits the smooth function of the markets. This includes the restrictions on borrowing, lack of human capital, and non-convex production technology. For example, if the technology is an increasing function on capital stock, it can result in a S-shaped capital accumulated equation. kb is an unstable fix point (threshold). For any country, whose initial endowment is less than kb, it will reach the lower equilibrium. For any country, who’s initial endowment is not less than kb, it will reach the higher equilibrium. This implies that to escape from the lower equilibrium, external aid is needed to provide the locals with sufficient initial capital.

Based on frictional-driven poverty trap theory, governments and NGOs implement policies such as building infrastructure, providing microfinance support, education, training, and direct capital subsidy.

Comments

Poverty trap theory influences modern anti-poverty policies. It has a striking implication that poverty can be eliminated by one-time efforts, which can help the poor break out of the trap and automatically reach a different equilibrium. While the theory is compelling, the results of poverty alleviation programs are mixed when in the absence of natural resource- and culture-related policies.(6;7). Lotus Project has developed a framework to sustainably incorporate natural resources and preserve key cultural values. We do this by building integrated value chains at a local level. These efforts have shown to support an increase in socio-economic status of local and marginalised communities.

Footnotes

Azariadis, C., & Stachurski, J. (2005). Poverty traps. Handbook of economic growth, 1, 295-384.

Solow, R.M. (1956). “A contribution to the theory of economic growth”. Quarterly Journal of Economics 70,65–94.

Sachs, J., McArthur, J. W., Schmidt-Traub, G., Kruk, M., Bahadur, C., Faye, M., & McCord, G. (2004). Ending Africa's poverty trap. Brookings papers on economic activity, 2004(1), 117-240.

Ghatak, M. (2015). Theories of poverty traps and anti-poverty policies. The World Bank Economic Review, 29(suppl_1), S77-S105.

Banerjee, A. V., & Mullainathan, S. (2008). Limited attention and income distribution. American Economic Review, 98(2), 489-93.

Hussaini, M. (2014). Poverty alleviation programs in Nigeria: Issues and challenges. International Journal of Development Research, 4(3), 717-720.

Bauchet, J., Morduch, J., & Ravi, S. (2015). Failure vs. displacement: Why an innovative anti-poverty program showed no net impact in South India. Journal of Development Economics, 116, 1-16.