The Rural Decline: The Vietnam Case Study

Introduction

This blog is a brief description of the rural-urban gap in Vietnam. It starts from a short capture of Vietnam’s modern history, then illustrates with some data to show the unbalanced development, and finally ends with a discussion of the local rural tourism industry. It should be noted that there are not many research papers related to Vietnam’s rural-urban gap in English. Further research or translation is needed.

Socioeconomic state of the country

Vietnam went through prolonged warfare throughout the 20th century. After World War II, France returned to reclaim colonial power in the First Indochina War, from which Vietnam emerged victorious in 1954. The Vietnam War began shortly after, during which the nation was divided into the communist North, supported by the Soviet Union and China, and the anti-communist South, supported by the United States. Upon North Vietnamese victory in 1975, Vietnam reunified as a unitary socialist state under the Communist Party of Vietnam in 1976. An ineffective planned economy, trade embargo by the West, and wars with Cambodia and China crippled the country. In 1986, the Communist Party initiated economic and political reforms, transforming the country to a market-oriented economy.

Vietnam is a unitary Marxist-Leninist one-party socialist republic. Although Vietnam remains officially committed to socialism, its economic policies have grown increasingly capitalist. Under the constitution, the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) asserts their role in all branches of the country's politics and society. The president is the elected head of state and the commander-in-chief of the military, serving as the chairman of the Council of Supreme Defence and Security, and holds the second highest office in Vietnam as well as performing executive functions and state appointments and setting policy.

In 1986, the CPV introduced socialist-oriented market economic reform program. Private ownership began to be encouraged in industry, commerce and agriculture and state enterprises were restructured to operate under market constraints. This led to the five-year economic plans being replaced by the socialist-oriented market mechanism. As a result of these reforms, Vietnam achieved approximately 8% annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth between 1990 and 1997. Also, the United States ended its economic embargo against Vietnam in early 1994. Deep poverty, defined as the percentage of the population living on less than $1 per day, has declined significantly in Vietnam and the relative poverty rate is now less than that of China, India, and the Philippines.

As Kerkvliet points, this experience of ‘rural transformation’ is broadly common to its neighbouring countries. Transformation is not simply about change in agricultural production or shifts in the distribution of resource and population, but includes issues of wealth distribution, social justice, the fiscal capacity of rural institutions for governance as well as health, education, agricultural extension, and rural credit. Economic liberalisation has touched each of these aspects of rural life. Proponents presume that these changes are positive. Rural development, in this sense, is understood also in the language of catching up, ‘efficiency,’ ‘integration,’ and a host of other terms common within the discourse of economic liberalisation.

Assessment of rural-urban dependency

In the late 1980s and the early 1990s, the Vietnamese government embarked on an ambitious program of economic reform called Doi Moi, or renovation. The aim of the reform was to transform the centralised state-planned economic system into a more decentralised and market-oriented economy in which the private sector was the key driver of growth. However, some regions benefited more than others. The Gini inequality just pays the full cost in most instances. This institutional restriction plays a negative role in preventing rural people moving to cities to work. The index increased from 0.32 in 1993 to 0.36 in 1998. The data reveals that most of this increase in inequality came in the form of a widening gap between rural and urban areas. Using the decomposable Theil inequality index, Fesselmeyer & Le find that over the 1993–1998 period the within-rural and urban inequality was almost unchanged (a minor increase of 0.6 percent), whereas the between-rural and urban inequality increased by 61.9 percent.

Another issue that is somewhat unique to Vietnam is its household registration system, which is used by the government to regulate internal migration. Liu & Dang (2019) shows that the system classifies the citizens into four different groups and determines the rights of an individual and their family’s access to social service. Permanent residents have unlimited access to the local social service, while the temporary residents.

Key findings

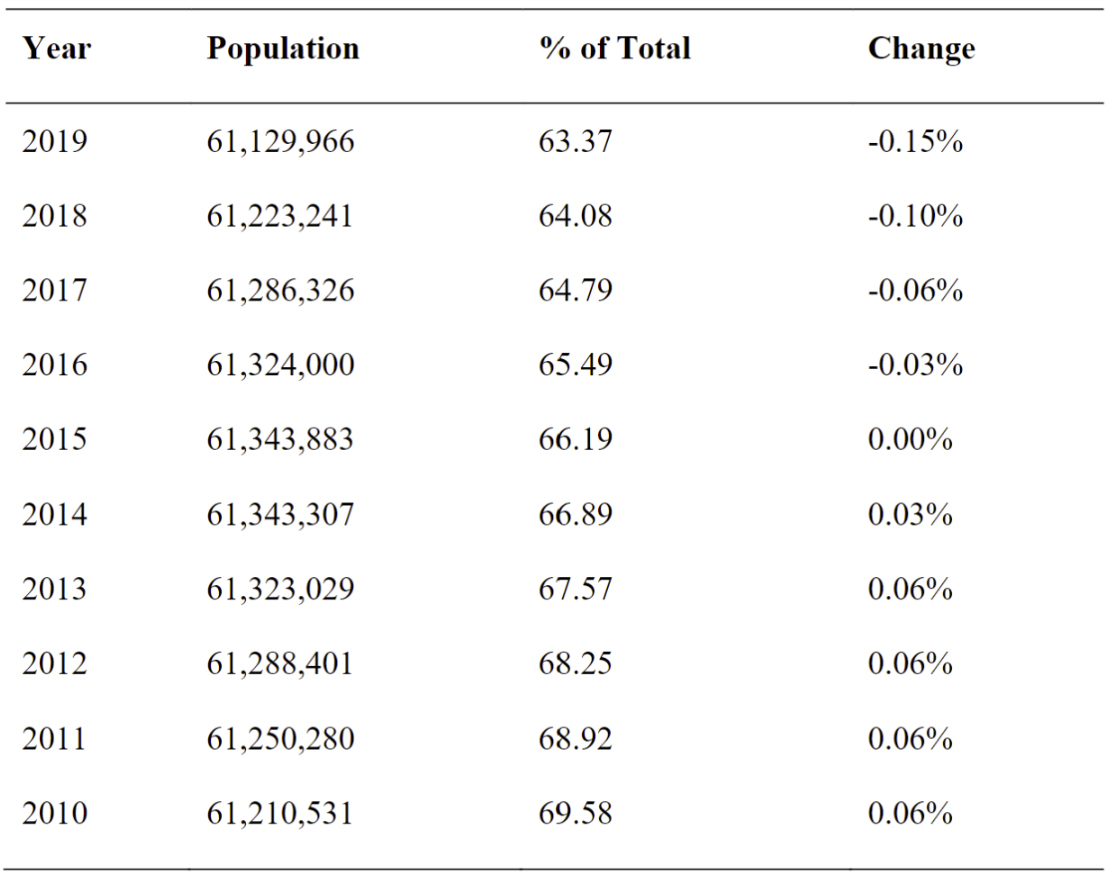

Table 1: Vietnam Rural Population (Holroyd & Coates,2021)

Holroyd & Coates (2021) explores the rural-urban transitions that have been taking place in Vietnam over the past two decades. During this period, Vietnam has been one of the most dynamic and fastest-growing economies in Asia, with an average GDP annual growth rate of over six percent between 2000 and 2020. During this time, the country’s largest cities have expanded dramatically. Hanoi’s population grew from 1.7 million people in 2000 to 4.7 million in 2020. Ho Chi Minh City, similarly, saw its population almost double from 4.4 million people in 2000 to 8.6 million in 2020. Haiphong increased from 600,000 in 2000 to 1.3 million people in 2020. The rural population, expressed as a percentage of Vietnam’s total population, fell by more than 12% in the same time period. While Vietnam remains a predominantly rural country, with over 61 million people, or over 63% of the population, still living in non-urban settings in 2019 (See Table 1), a rural-urban transition is underway.

Both urban and rural Vietnam have undergone dramatic improvements over the past three decades, but this has led to an increase in rural-urban disparities. The Vietnam Household Living Standards Survey 2018 reported the monthly average income per capita as 5.62 million Vietnamese Dong (approximately US$244) in the urban areas and 2.98 million Vietnamese Dong (approximately $129) in the rural areas—a major gap. The percentage of households using tap water in 2018 was 78.4% for urban areas and only 25.3% for rural ones. There is a significant difference in the number of durable goods per 100 households in urban versus rural areas. The northern midlands and mountain areas have the highest poverty rate in the country, 18.4%, followed by the central highlands at 13.9%. The country’s ethnic minority populations, many of whom live in those areas, are particularly economically badly off. In 2016, ethnic minorities were only 14 percent of the population of Vietnam, but they represented 73 percent of those in serious poverty.

Is Rural Tourism a solution?

Table 2: Number of Tourists (Million) in different years. Source: http://b-company.jp/en/tourism-situation-en

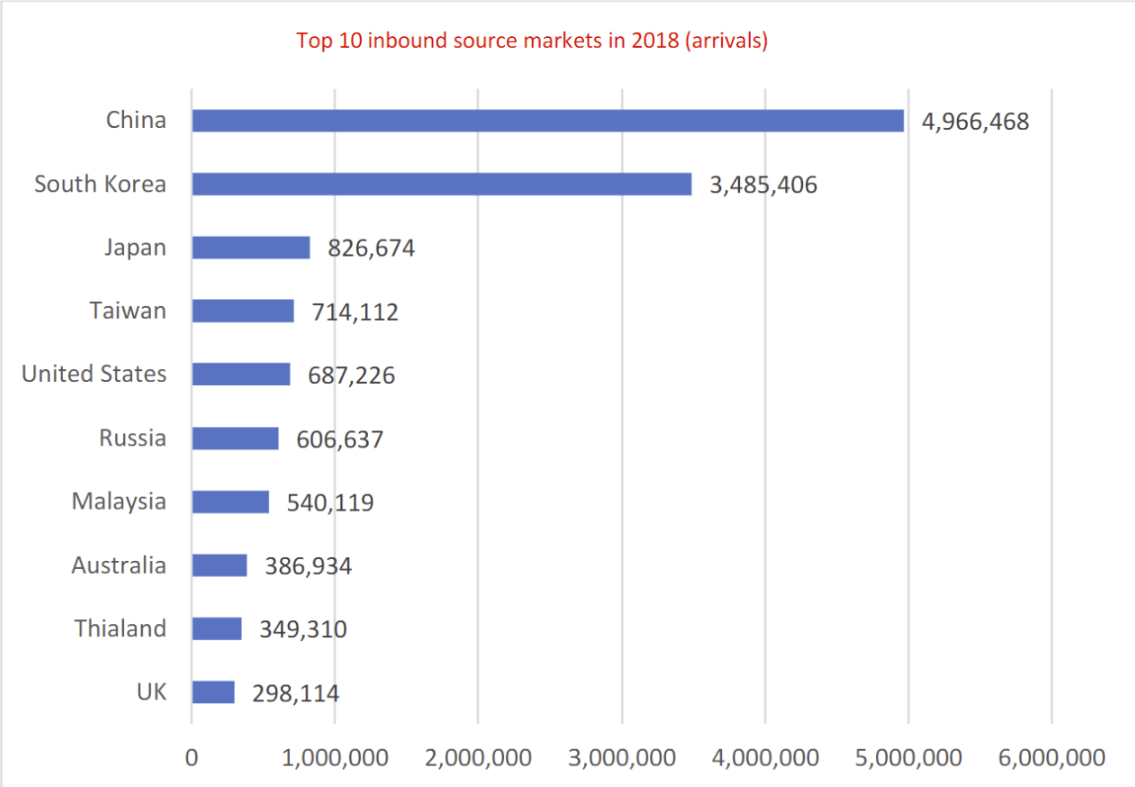

Tourism is a sector of growing importance to Vietnam, including for many parts of rural Vietnam. The number of international visitors to Vietnam has grown dramatically over the past decade, nearly doubling between 2014 and 2018 (see Table 2). Domestic tourism is also on the rise. Tourism to rural areas focuses on some specific regions (some of which are discussed below), beaches, caves, day trips outside of Hanoi, to the Mekong Delta outside of HCMC, to battlefields or other sites related to the Vietnam War.

Many of Vietnam’s most famous tourist destinations are in rural parts of the country. Three of these destinations—Sapa, Ha Long Bay, and Dalat—have grown dramatically in popularity over the past twenty years and have brought economic benefits to the rural areas that surround the cities.

Table 3: Vietnam’s International Visitors from different countries. Source: http://www.vietnamtourism.gov.vn/english/index.php/items/14214)

It is evident that rural Vietnam is not homogenous; there are big differences in the level of economic development in the various rural areas of some provinces. Those remote and rural regions that are overwhelmingly agricultural, mountainous, isolated, and vulnerable to natural disasters are the least well off. Areas that attract tourism, industrial and/or commercial investment, have rich agricultural lands, even though they are located well beyond the prosperous urban regions that are improving at a much faster rate. The impression, widely shared by government officials, teachers, and community leaders, is that most rural regions are falling well behind the major metropolitan areas, which have been experiencing rapid growth and improved quality of life.

Conclusion

There are regions in which rural areas are prospering and from which not only are people not leaving but to which they are moving. There are others, in the central and northern highlands in particular, that remain extremely poor. It is impossible to ignore both the marked developments taking place in rural areas and small towns and the growing gap between the levels of prosperity in urban and the most remote rural areas.

The Vietnam situation suggests that a shift to a more nuanced understanding of rural/urban relationships is required. Remote regions have vastly different opportunities than those proximate to major cities. Parts of rural Vietnam fit some, but not all, of the general patterns of rural decline. Out-migration of young people is a serious challenge, and slow rural depopulation is a fact of life across the country. Educational deficiencies are piled on top of other challenges, including the diseconomies of scale and widespread problems with infrastructure in such areas as roads, airfields, docks, electricity, and the Internet. Rural regions, especially in developing countries, can be especially vulnerable to natural disasters.