How Cash Cropping Can Improve the Lives of Smallholder Farmers in Vietnam

Smallholder farmers in impoverished areas traditionally farm staple crops, such as rice, to feed themselves. This subsistence farming usually maintains the farmers’ basic lifestyle, but does not bring economic growth. Instead, economic growth oftens comes from the practice of cash cropping: where a farmer grows and sells commercial crops on the open market.

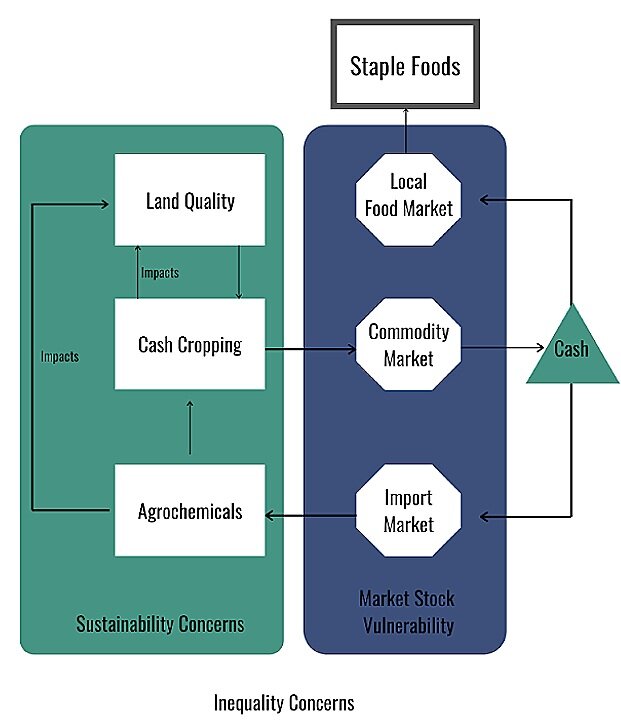

Cash cropping is an opportunity for the smallholder to bring in cash and raise their income, however this comes with the potential costs. These include vulnerability to economic shocks, increase in inequality and a reduction in environmental sustainability. Tackling the costs of cash cropping is a key part of Lotus Project’s Rural Development Model (RDM).

Cash cropping has been successful in raising farmers’ incomes in parts of Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam. In particular, it has brought higher incomes to areas with good market access and good infrastructure. This was the case for Southern Laotian farmers with access to land and proximity to markets. These maize-growing farmers earned higher incomes when compared to the subsistence rice farmers in less-accessible Northern Laos. The parts of Thailand and Vietnam with higher market access also had higher income.

Yet for these areas, environmental sustainability is a key concern. After all, cash cropping involves intensive agriculture, where agrochemicals are liberally used and the land is not rested between planting seasons. Here, farmers face soil degradation and erosion as they continue cash cropping.

These cash cropping farmers are also more vulnerable to economic shocks. These farmers sell their crops on the open market and then buy food. Thus, any change in the sale price of cash crops can impact the farmer’s livelihood. In fact, when the price of maize dropped in 2008, cash croppers in northeastern Laos actually switched back to subsistence rice farming.

Finally, rising inequality is a potential problem. A study in Vietnam showed households both exiting and entering poverty when they adopted cash cropping. Ethnographic work in Indonesia also saw more inequality in a community of farmers that adopted cacao cash cropping. In fact, less successful farmers were forced to sell parts of their land to make ends meet.

Cash cropping is a mixed bag. Here, the Lotus Project’s locally informed strategy development approach aims to mitigate the disadvantages. The RDM focuses on the geographical context as well as the surrounding business and economic context. With the geographical context, we can understand the viability of specific crops and the environmental sustainability issues; whereas, with the economic context, we can understand the market demand for cash crops as well as the non-farm opportunities in the area.

GEORGE CHEN